Everything About How I Study Craft On My Own: Tips and Ideas

At this point in my journey, my most concrete goal as a student of poetry is to become more comfortable articulating what I love about a poem. I am afraid of wielding words—that are full of meaning and nuance—as empty language, or worse, as a spectacle of my poetic knowledge.

Instead, I am interested in finding language for what stirs something in me in a way that feels authentic and clear. I also know that if I lean on keywords, I am limiting the way I can look at a poem’s strengths.

I am in search of a more expansive approach to understanding poetry’s mystique that grounds itself in intuition while building on all of the poetry I have read over the years. I even hope to find or make new language for what happens in a poem as well as how it happens.

I am not the only one interested in this kind of approach to craft. I remember hearing Angel Nafis talking about how her MFA experience helped her find the language for what she already knew as a reader and writer of poetry intuitively.

Just hearing her say that was a major turning point for me because it gave me permission to believe that I already hold poetic knowledge and have so much to learn about poetry by paying attention to my intuition. How I choose to craft a poem—each revision I make without knowing exactly why—is poetic knowledge, likely rooted in everything I have read leading up to this point.

Her comment also made me feel empowered to find my own way toward understanding the wisdom my intuition carries.

I also like to keep in mind Joy Priest’s definition of craft: “the sustained attention that distinguishes poets from those who occasionally write poems.” I highly recommend reading Priest’s “Craft In Not Objective” (to any one at any point in their journey) for its fresh and complex perspective on craft. This is where she also writes, “This must be a spiritual practice, this craft thing.”

Like many folks out there, I know I cannot commit to an MFA program at this point in my life (in more ways than one). As someone who enjoyed designing curriculum as a middle school teacher, I am embracing this opportunity to create my own poetry self-study process and path.

Now, let’s get into the nitty gritty: how I make time to study, the tools that have become central to my practice, and the ways I like to challenge myself.

My Study Schedule & Time-Task Tracking

I am a full-time stay-at-home mother, so this is my messy writing & study schedule:

Before my kids are up (5/6am - 8:30am)

Some nap times (1pm - 3pm)

One or two mornings per week when my husband is home (8am - 12pm)

My free weekly Creativity Circle when we gather online to create in community (Sundays, 1pm - 2:30pm)

If I have a chunk of 2-3 uninterrupted hours, this is my agenda:

Craft-focused reading and notes (45 minutes)

Read poems with a more focused attention—many times, rereading poems or rewriting them by hand in my “Messy” Notebook (30 minutes)

Freewrite (15 minutes)

Use the freewrite to make a poem OR edit poems (30 minutes)

Time-Task Tracking

I rarely get that much uninterrupted time and still struggle to get into a weekly routine. A practice that is helping me cope with that struggle is tracking how I use my time every day, which I learned while working one-on-one with Shira Erlichman. For this practice, I use a passport-sized full year weekly planner ↗ that has many extra pages on the back.

More planners I love:

I use the planner part to write down my favorite lines of the poems I read each day and use the blank grid pages in the back for noting everything I do that nourishes my creativity. I start by writing the date and time.

Then, I write what I am doing: reading danez smith poems, exploring literary magazines, listening to an episode of Between the Lines, submitting poems, working on __ application. I write my end time when I complete that task or set of tasks.

A lot still goes unwritten, like when I am reading Poets & Writers while my kids work on puzzles, but I try to honor every time I show up for what I love most by writing it down as much as possible.

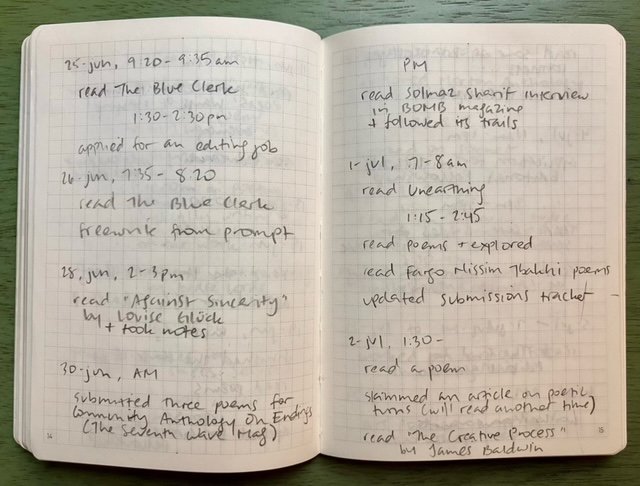

Two pages of my Time-Task Tracking

Above I share an example of what this looks like for me. I want to highlight my note about reading Solmaz Sharif’s interview with Alina Stefanescu in BOMB Magazine where I also added “& followed its trails.” I think “following tracks” would more accurately describe what I was doing by searching for almost every text and writer than Sharif mentioned in this interview.

This is what I most enjoy about not having way too many texts assigned to me by someone else along with a wildly stressful deadline. I can let my curiosity lead. I can read or listen to one interview and decide freely, “I want to read another one!” (Thank you, internet!)

More Study Tools

In addition to my little planner, I have several other notebooks and tools that I use for my poetry-focused studies.

What lives in my Craft Notes Notebook (I use a Hardcover 5.7 x 8.5 in Sketchbook):

My notes (mostly a bunch of quotes) from books, essays, and interviews about poetry

Poems that I want to keep studying

Clips from magazines that I want to keep close

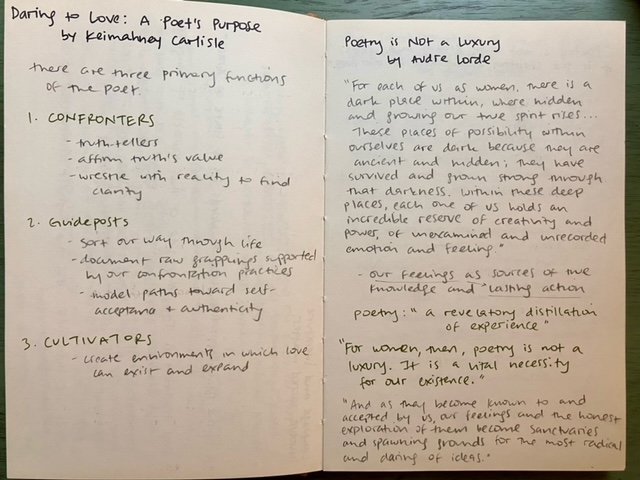

Two pages of my Craft Notes Notebook

What lives in my Messy Notebook (I use Blackwing A4 Spiral Dot Grid Notebook, more great options below!)

Freewrites

Handwritten poem drafts

Poem-mapping for workshops

Quick notes from workshops or live craft talks

I like to challenge myself by identifying connections between poems, which is why I keep growing lists of poems by category (themes, forms, strong examples of a specific craft element, etc.) using Google Docs. These lists help me ground some poetic concepts by collecting strong examples, and I always feel like I am learning when I am making connections.

I also prefer designing study cycles with a specific focus. Most recently, I chose to study the ars poetica, so I researched every text I could find about the ars poetica and created this Craft Study Schedule for that cycle and built on that document to design a ten-week generative poetry workshop.

I love casually and accidentally finding more examples of the ars poetica to add to my list. In that way, this cycle of study never ends. I am planning to focus on surrealist poetry next!

More notebooks I love:

Seeking Challenges in MFA Applications

Even though I am not ready to apply for MFA programs yet (and, to be clear, I know nobody has to get an MFA to be a fulfilled poet), I like to look into different programs and application requirements in anticipation.

In some applications, I have found tasks that piqued my interest and that I want to try for practice and challenge. For example, Pacific University’s MFA application asks for a “short critical essay about a piece of published writing…that reveals your ability to write thoughtfully and with focus on another writer’s work while exploring some aspect of craft.” They also included questions for guidance. I immediately thought: I want to write one about Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky and The World Keeps Ending, The World Goes On by Franny Choi. I will be looping these critical analyses into my self-study with self-imposed deadlines.

I would also like to suggest an alternative approach to practice writing about poetry: book reviews. If I were taking this approach, I would study book reviews that I like (I enjoy reading Emily Brandt’s short reviews in their newsletter Open Language) and use them as templates to write my own.

Books on Craft

The Poetry Lab’s Resource Center and Podcast offer great resources for building your own reading list.

I also highly recommend How We Do It: Black Writers on Craft, Practice, and Skill edited by Jericho Brown. I am currently reading Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World by Jane Hirsfield (on the Libby app) and writing down so many gems just two chapters in. I found this book after rereading one of her interviews in an old copy of Poets & Writers.

I recommend going to a physical bookstore or library (if possible) or checking out books through the Libby app so that you can get to know a book as much as possible before purchasing it or committing to reading it.

So far, I have learned the most about how to read a poem by reading poets’ analyses and reflections on specific poems. For this reason, I want to highlight Poetry Unbound by Pádraig Ó Tuama and Raised By Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems as surprisingly useful resources because each poem is followed by a reflection in prose that speaks to the craft and impact of each poem.

Don’t Forget to Write a Poem

— I tell myself over and over again.

In some ways, poetry feels like a puzzle I will never figure out. There are no benchmarks for me to reach and declare: “I have mastered the enjambment,” or “I know how to choose the perfect title with ease.”

The way each poet works with language is so complex, if not innovative in itself. It has been really important for me to remember that as I try to wrap my mind around the art of poetry. It is intimidating for me, and it can be easy to focus on consuming as much information as possible. This brings me back to Joy Priest’s “Craft In Not Objective,” which concisely breaks down the ways that “official knowledge” can ultimately be used as a tool of avoidance. She offers the practice of noticing as an alternative.

I believe that we can also learn a lot from the choices we make in our own poems, especially in the process of editing. I believe that we can truly work with our intuitive poetic knowledge and work through what we are learning from others by actually writing a poem and another and another.

This article was published on October 15, 2024. Written by: